In our previous interviews, we have gained some great insight into youth coaching from the perspective of coaches at many different levels and ex-players who have gone into coaching later in their careers.

But what is it like for a young player today taking their first steps on the road to becoming a professional footballer? How are they treated by the top youth soccer academies? And what happens when they are rejected or their career is hampered by injury?

To find out more about player welfare, dealing with setbacks and embracing life beyond the field of play, we spoke to former youth soccer academy member, student and budding coach Jack Burns.

Interview with Former Academy Player, and Kinesiology and Sport Management Graduate Jack Burns

? Hi Jack, thanks for taking time out of your busy schedule to talk to Ertheo. To kick things off, can you tell us a little bit about yourself, your background and what you are doing now.

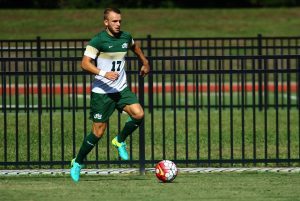

My name is Jack Burns, I am 23 years old and I come from Portsmouth in the UK. I was a former youth soccer academy player at Chelsea and Portsmouth, and a former student-athlete with Jacksonville University’s NCAA Division 1 Men’s Soccer Team.

I am a graduate student of Kinesiology and Sport Management at Jacksonville University, Florida. This year I’ve accepted a business internship working for the President of JU and I will also be studying my Kinesiology Masters this September.

? As a young player, what were your expectations in regards to your career path and how were those expectations managed on a professional level by those responsible for your development?

First and foremost, I was extremely fortunate to grow up and develop in professional academies, like Portsmouth and Chelsea, with great coaches and mentors. My expectations and goals were aligned with those of my teammates, coaches and club, with the ultimate goal of becoming a professional player. However, I suffered multiple long-term injuries and therefore my goals changed as I matured, as did the expectations of those around me.

In retrospect, there were certain aspects that were neglected by myself and my coaches, education being the standout one. Since leaving the academy scene in 2012, I have seen progress made in this area. But although things are moving in the right direction, I think more can still be done.

Related reading: Steps to becoming a professional football player in Europe

? During your youth soccer academy years, did your feel that all young players were judged fairly on their ability or did you feel that there was an element of favouritism at play?

Favoritism is a tough word to use, but there are of course unconscious biases. I could honestly say these biases sometimes worked in my favor, but occasionally, they worked against me too. There are a lot of variables when we discuss biases.

For instance, the club’s philosophy may lean towards a competitive and winning mentality, causing coaches to field better players for longer, rather than distributing playing time.

Or an academy may be more bias toward players who have benefitted from monetary investment. Sometimes this would pay off, but at other times it would restrict the development and reduce opportunities for other players.

Related reading: Your BEST CHANCE at becoming a professional soccer player

? Do you feel that players were expected to fit into a certain psychological profile at the academies? If so, do you feel that this approach could actually hinder the development process of some players?

I believe there are certain socio-cultural expectations when considering psychological profiles. However, I don’t believe these ideas are restricted to the personnel within soccer clubs, but branch further out into the wider culture in which we grow up and operate. I certainly felt a degree of expectation to fit the “footballer” profile during my career. That pressure to think and act in a certain way proved too much for me at times.

My trajectory over the past couple of years has been to move away from those expectations and become an advocate for player welfare. During this time, I began to feel more comfortable in my own skin and started to enjoy playing more and my game actually improved.

To answer the second part of the question – yes, I do believe psychological expectations hinder developmental processes, not only from a soccer-specific standpoint but also from a welfare perspective. Unfortunately, in society, and particularly in sports, there are intense masculine constructs that are often over-emphasized and valued. It’s my opinion that the lack of understanding in areas such as vulnerability and social courage can devalue a player’s potential.

? How was your release handled by the club and what support or advice was offered?

The academy staff were a different class when I left, particularly our education and welfare officer, Jon Slater, and academy head physio, Sean Duggan. They became mentors for me and are now friends. Their help and guidance went above and beyond. However, I feel my treatment may have been slightly different to that of others. And, although I was interested in pursuing avenues away from the professional game, I still don’t believe there is enough done to help players during that transitional period.

? How did your release affect you personally?

My release helped me to grow and to be honest, it humbled me, even though I was expecting it. My time at Portsmouth had been plagued with two serious knee injuries, resulting in three surgeries and like most, I had to drop down a few levels.

That time between my release and my move to the US really tested me. I worked as a plumber full-time and played semi-pro. It opened my eyes to the real world – something I hadn’t truly understood before.

In retrospect, the only thing I believe that could have been done better at the time would have been to have more check-ins from the club and the PFA. I can’t recall any official contact from the club or the association and that lack of ongoing support may be a huge factor in why many drop out of the game, struggle to find employment or do not enter higher education.

? In your experience, do you think there is sufficient focus on player welfare in the UK, especially at youth level, and is there any kind of support network to help those who are rejected to find their feet in life?

I don’t believe so. Those who are in the roles that do exist are doing an amazing job; however, I feel that more could be done. The welfare systems in place in collegiate athletics in the US are far superior, but even they have a long way to go until they’re sufficient.

Related reading: Your BEST CHANCE at becoming a pro soccer player in the USA

I don’t have the answer, right now, but it’s my hope that through my education I can begin to comprehend these problems and develop solutions.

There are support networks, such as the aforementioned PFA, and they have some great staff members, initiatives and services but there’s something missing. That could be down to the lack of priority on welfare from the clubs who, after all, have the most contact time with the players.

? What did you do following your release and before your move to the US?

Like most youth team players, I trialed at a few clubs up and down the country and attended the LFE’s “Exit Trials,” all to no avail. I ended up a small non-league club in the Portsmouth area, where I played until my move to the US nine months later.

? How did you adapt to studying and playing abroad?

It was tough. As a player, I’m fortunate enough to be a good decision maker, and technically and tactically sound, but it was the physical aspects of the game in the US that was the greatest challenge. The physical demands aren’t related to tough tackling and aggressiveness like in the UK, but more to player conditioning – and I’d never experienced anything like it. The intensity the games are played at is immense and this, coupled with playing in the Florida region in temperatures that would regularly exceed 35 degrees, made it hard to adapt.

The studying aspect was okay for me. I was always comfortable as a student at school and in our educational program at Portsmouth. However, I never pushed myself as I had never thought of education as something I needed, wanted or enjoyed, so I just coasted along. It wasn’t until the beginning of my third year (of four) at University that I really took a vested interest in my education and school became more important.

The more I invested, the more I enjoyed it and I gained a sense of fulfillment from my education that soccer had been unable to provide me for a long time. My education at Jacksonville University has been second-to-none; not only in the classroom, but also on the pitch, in my relationships and interactions around campus, and on professional level.

? You experienced further setbacks (on a sporting level) during your time in Florida, how did you cope during this period and what support was available to you?

Yes, like anyone in any walk of life, I experienced setbacks and some tough times. For a long time, these struggles were often things I kept to myself and swept under the carpet, but as we know, they come back to bite you down the line. However, I overcame them thanks to my amazing support network at Jacksonville University that included my coaches, my friends, my girlfriend, my family and the JU Student-Athlete services staff. They created an environment where I felt comfortable to be vulnerable and talk about my issues.

Ultimately, it was them who opened my eyes a little to the bigger picture and began to advise me and care for me. They created an environment where I felt content and could rediscover myself.

? Do you believe that studying and training in a multi-cultural environment such as the one at Jacksonville allows for greater expressiveness and can aid personal development?

One hundred percent. In a society where one particular culture dominates you begin to, consciously or subconsciously, tailor you behaviors to fit in with the social norms. Experiencing greater diversity allowed me to see different ways to live life – good or bad.

You begin to adopt aspects that you like and embrace those that make you who you are. I was the only British player in my team at JU, and one of only three Brit’s out of 500 student-athletes, across 19 teams. So that allowed me to really develop as a person.

The diversity was not just limited to our origins but also to our intellect. Being able to hear different opinions on politics, religion, values and tactics was great. Looking back at my youth, I can see that I was extremely ethnocentric towards Britain but now, after being engulfed in other amazing cultures, I struggle to identify with many customs and cultural values of my country.

? Have you noticed a difference in the basic approach to soccer coaching in the USA compared to the UK and if so, what are the main differences?

There are great differences. Most notably, the quality of football content provided by the UK-based coaches when compared to the US-based ones. However, the US coaches have a greater interest in the players’ development as human beings. There is definite room for collaboration between the two styles.

? How have your goals and ambitions changed since moving to the US?

Drastically. My first and only goal was to become a professional football player and I maintained that goal up until that pivotal third year of my studies in the US.

It was then that academia and education began to open my eyes to what I wanted to do for the rest of my life – to focus on player development.

My aim is to take all of the things I’ve spoke of today and put them into practice on a professional level.

I’ve now completed my undergraduate degree in Sports Management and am pursuing a graduate’s degree in Kinesiology, with the hope of moving onto a doctorates degree further down the line.

Related reading: How to earn a soccer scholarship to study and train at a U.S. university

? If you could change one thing about the way you were coached and handled as a young a player, what would it be?

I would want to have more fun! Moving into Chelsea’s academy structure as an 11 year-old, I began to train and compete, I no longer just played. I believe that the pressure I placed on myself to achieve my professional goal may be the reason I’m no longer playing today.

? Do you think that a more open-minded approach to player welfare could actually improve standards at youth soccer academy level and beyond? For instance, by creating a situation where players are better prepared for life in general and less overwhelmed by the fear of failure at sport.

For sure, I’m in no doubt that’s the case. People may think that by allowing for an environment that embraces player welfare you are sacrificing the competitive nature of the sport that we love, but I believe the opposite. I believe that they fuel one another and enable optimal performance.

Related reading: Training to become a professional player in a healthy environment

? And what crucial piece of advice would you give to any aspiring young athlete today?

I’d tell them to challenge themselves to develop outside their chosen sport. To embrace education, foster meaningful relationships and don’t waste the opportunity to grow each day. And finally, don’t lose sight of what makes you, you.

As well studying towards his careers goals, Jack Burns is the co-author of the blog sonderssecret.com and can be found sharing his thoughts on Instagram and Twitter.

Do you want to become a professional soccer player?

Whether you’re training to become a professional soccer player in the United States or in Europe, it’s important to explore your options for attending advanced professional level training while continuing your education.

High performance football academies in Europe or the FC Barcelona USSDA high performance academy are your absolute best options to earn a world-class education while highly increasing your chances of becoming a professional soccer player.

While it’s true that only 1.4% of soccer players who play in the NCAA go on to become pro soccer players (NCAA), and less than 1% of all the boys who enter a European soccer youth academies become professional soccer players, don’t forget that every graduate from the FC Barcelona USSDA high performance academy has earned a college scholarship or signed a professional contract.

Work hard to improve your skills by playing for youth teams, attending summer soccer camps abroad, and/or playing for a USSDA. Then join a high performance soccer academy in Europe or the USA.

You won’t regret your decision to invest in your future on the soccer field, in the classroom, and eventually in the workplace.

For more information about any of these programs or advice about which high performance academy is best suited to your needs, don’t hesitate to contact us.

You can also send us an email directly to [email protected] or you can give us a call at: